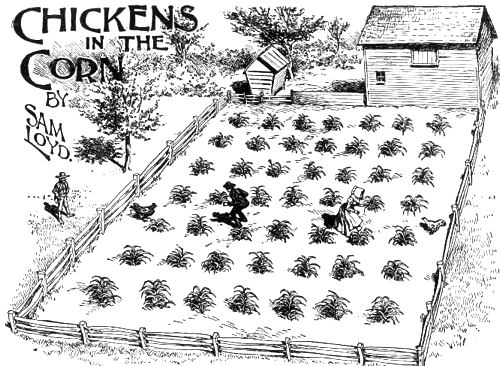

IN WATCHING THE gambols of playful dogs, kittens and other domestic animals we are often impressed by the way they seem to enter into the spirit of the fun and enjoy the fine points of play, just as human beings do, and it is easy to detect a certain appreciation of the sense of humor in the exultation over the defeat or mishap of a playmate. But for a rollicking exhibition of mischief, or “tantalizing cussedness,” as the farmer calls it, I have never seen anything equal to the sport, produced by two obstinate chickens, refusing to be driven or coaxed from a garden, they neither fly nor run, but just, dodge about, keeping close to their pursuers, so as to be out of reach. In fact, when the would-be captors retreat the chickens become pursuers and follow close upon their heels, uttering sounds of defiance and contempt.

On a New Jersey farm, where some city folks were wont to summer, chicken-chasing became a matter of everyday sport, and there were two pet chickens which could always be found in the garden ready to challenge any one to catch them. It reminded one of a game of tag, and was in many respects so like my old “Pigs-in-Clover” that I was continually twitted to “work it into a new puzzle.” I have really concluded to illustrate a curious puzzle point suggested by those sportive chickens, which otherwise I should never have thought of, and which I am satisfied will worry some of our experts.

The object is to prove in just how many moves the good farmer and his wife could catch the two chickens.

The field, is divided into sixty-four square patches, marked off by the corn hills. Let us suppose that they are playing a game, moving between the corn rows from one square to another, directly up and down or right and left.

Play turn about—first let the man and woman each move one square—then let each of the chickens make a move, and the play continues by turns until you find out in how many moves it is possible to drive the chickens into such a position that both of them are cornered and captured.

Sketch out a diagram containing 49 corn hills and show upon it by drawing lines how you believe the chickens may be captured in the shortest possible number of moves.

The real point of this puzzle is that, play as you will, the “man” could never catch the “rooster” nor the “woman” the hen, for, as they say in chess or checkers, the rooster “has got the move” on the man, and for the same reason the woman can never get the “opposition” on the hen. But if they will reverse matters the answer is very simple—the man can catch the hen in nine moves and the woman will catch the hen in eight. The principle can best be shown on a checkerboard: First move the man toward the woman, and the woman toward the man. Both birds move, following their would-be captors. Now move the man down one square and move the woman to the square above him. After that transposition has been effected the continuation is simple. The birds each move and are closely pursued until captured.

2. A CHARADE.

My sportive first bound lightly o’er the lawn;

While my second does its Owner’s brow adorn;

The cheering spirit, of my whole may prove,

A good Samaritan thy pains to soothe.

Cypher Ans. 8, 1, 18, 20, 19, 8, 15, 18, 14.

HARTSHORN

3.

Why is the letter D like a sailor? Because it follows the C.

When is a fowl’s neck like a bell? When it is wrung for dinner.

Name the richest child in the world? Rothschild.

When is a butterfly like a kiss? When it alights on tulips.

[Page 186]