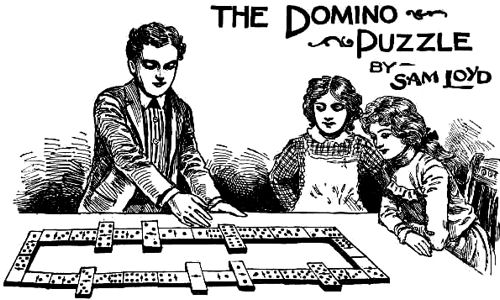

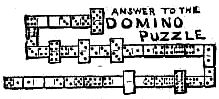

I USED TO BE VERY fond of dominoes, and flattered myself that I could put up a pretty stiff game of straight muggins, but it was my privilege to meet a certain Monsieur Blume, in Paris, who speedily disillusioned me of the notion that I knew anything about the science of dominoes. He was a professional player, of about 80 years of age and had been blind from birth. He made a living by going about the cafes, giving exhibitions of his wonderful play in which he gave phenomenal odds to all opponents. I have upon several occasions alluded to the fact that every game or pastime is susceptible of furnishing a series of problems or puzzles, as in whist or chess, which illustrate in an instructive way the peculiar strategy of the play. M. Blume would always finish a game of dominoes after the manner of a problem, in that he would announce that he would make exactly five, ten or twenty points, as the case might be, and it was this feature of the play which suggested to me the domino puzzle of: “What is the greatest possible number of points that can be scored by both players in the regular game of muggins wherein the two ends are counted whenever they add up five, ten, fifteen or twenty?” It may be mentioned to such of our puzzlists who may not have a set of dominoes conveniently at hand, that the sketch shows a complete set of twenty-eight stones, which may be utilized to solve the puzzle.

Just lay them down one at a time and count both ends whenever they add up to 5, 10, 15, or 20, and see how much you can make.

Patience and perseverance, combined with cleverness and a certain amount of luck, will enable a good domino player to demonstrate that — contrary to popular belief — 200 points might possibly be scored in a game of straight muggins, The problem ran the gauntlet of the mathematicians and experts some years ago, when, by careful analysis, the limit was raised to 195, But I afterwards discovered that by one pretty stroke of play, which seemed to have been overlooked in the discussion, five more points could be scored, which struck me as being worthy of being presented in puzzle form,

The play may be slightly varied, but is substantially as follows: First lead the three-two, and continue to build up so as to present the following lines: 5-5, 5-6, 6-6, 6-2, 2-1, 1-1, 1-4, 4-2, 2-2, 2-3, 3-3, 3-1, 1-6, 6-4, 4-4, 4-3, 3-6, 6-0, 0-3, 3- 5, 5-0, 0-0, 0-4, 4-5, 5-2, 2-0, 0-1, 1-5.

2. Domino Trick

While on the subject of dominoes I will explain one of the neatest parlor tricks you ever saw. Take a full set of the 28 dominoes and mix them up well, and unobserved by any of the spectators conceal one of the stones in your hand. Tell them you will go out of the room while they match the set in one long row, and you will tell them what the two ends will be.

Be careful not to select a double number. Mix them all up carefully and while doing so return the one you had, at the same time telling the them that the two ends were 3 and 1, or whatever numbers you had on the domino.

3.

Here is another puzzle which incidentally introduces two very interesting subjects: the origin of the game of dominoes and that ever popular theme of the magic square.

According to a well authenticated bit of history, two monks who had been committed to a lengthy seclusion contrived to beguile the dreary hours of their confinement without breaking the rules of silence which had been imposed upon them by building up magic squares with small fiat stones, upon which they had black dots like “dice.” The amusement gradually advanced into a species of a game of skill, and by a preconcerted arrangement between the players the winner would inform the other of his victory by repeating in an undertone the first, line of the vesper prayer. In process of time the two monks so far completed the set of stones as to represent every possible combination of two figures from double blank to double six and perfected the rules so as to make a most interesting game, so that at the end of the term of their incarceration it became generally adopted by all of the inmates of the monastery as a lawful and instructive pastime.

It soon spread from town to town and became popular throughout Italy, and the first of the line of the vespers was reduced to the single word Domino, by which the game has ever since been known.

An old writer on the subject says that the various combinations, or arrangements by which a number of the stones, being the same as our ordinary dominoes, might be formed so as to make magic squares which would add up the same in every direction, seems to have been lost, and its possibility has been questioned by eminent mathematicians. In this respect, however, the writer errs, for to modern puzzlists, who are familiar with the theory and construction of magic squares, the feat is an easy one, and as such I present it to our young puzzlists.

[Page 112]